My thirteen-year-old daughter left a note on the kitchen table asking me to please stay home from her school talent show. She didn’t call me Dad in the note.

She wrote “Mike” like I was a stranger. The reason was in the second sentence: “Everyone’s parents look normal and you’re going to embarrass me with your tattoos and your motorcycle and the way you look.”

I’m a fifty-one-year-old biker who’s covered in ink from my neck to my knuckles. I’ve got a beard down to my chest. I ride a Harley that sounds like thunder. And apparently, I’m too embarrassing for my own kid to be seen with.

My wife died when Lisa was six. Cancer took her in eight months. For seven years, it’s been just me and Lisa against the world.

I worked construction during the day and learned to braid hair at night. I figured out tampons and training bras and mean girls.

I showed up to every parent-teacher conference in my leather vest because it was the only thing I owned without concrete dust on it.

And now she was ashamed of me.

I sat at that kitchen table for an hour staring at her note. Then I called the school and asked if I could sign up as a performer in the talent show.

The music teacher, Mrs. Patterson, sounded confused. “Mr. Reeves, the signup deadline was two weeks ago. All the slots are filled.”

“Please,” I said. “It’s important. I’ll go last. I’ll take five minutes. I need to do this.”

Something in my voice must have convinced her. “Okay. You’re in. But Mr. Reeves, what exactly will you be performing?”

“A song I wrote,” I said. “For my daughter.”

I didn’t tell Lisa. The night of the talent show, I told her I had to work late. She looked relieved. Actually relieved that her dad wouldn’t be there. That hurt worse than anything.

I watched her leave with her friend’s mom. She was wearing the blue dress we’d picked out together, her hair in the French braid I’d learned to do from YouTube videos.

She looked so much like her mother it made my chest ache.

I showed up at the school an hour later. Mrs. Patterson met me at the back entrance with my guitar. She looked at my vest, my tattoos, my boots, and I saw her swallow nervously. “Mr. Reeves, Lisa doesn’t know you’re here, does she?”

“No ma’am.”

“She’s going to be mortified when you walk out on that stage.” Mrs. Patterson’s voice was gentle. “Are you sure you want to do this?”

I looked at her. “I’ve been Lisa’s dad for thirteen years. I’ve been both her parents for seven. I’ve made every breakfast, signed every permission slip, stayed up through every nightmare. I taught myself to braid hair and paint nails and talk about boys.” My voice cracked. “And now she’s ashamed of me. So yes, ma’am. I’m sure.”

The auditorium was packed. I stood backstage and watched kid after kid perform. Piano pieces. Dance routines. Magic tricks. And Lisa. My Lisa sang “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” in a voice that sounded exactly like her mother’s. She was beautiful and confident and when she finished, the applause was thunderous.

She was smiling as she walked offstage. Then she saw me standing in the wings.

Her face went white. Then red. “Dad, what are you doing here?” she hissed. “You can’t be here. You promised you had to work.”

“I lied, baby girl.”

“Dad, please leave. Please. Everyone’s going to see you and—”

Mrs. Patterson’s voice came over the speaker. “And for our final performance, we have a special addition to tonight’s program. Please welcome Lisa Reeves’ father, Mike.”

Lisa grabbed my arm. “Dad, no. Please don’t do this to me.”

I looked down at my daughter. “Sometimes being a dad means embarrassing your kid. But sometimes it means showing them who you really are.” I kissed the top of her head. “I love you, Lisa. Even when you don’t love me back.”

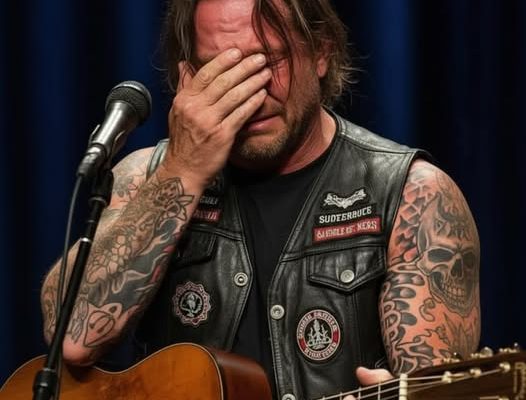

I walked out onto that stage with my guitar. The auditorium went silent. Two hundred people staring at the tattooed biker in the leather vest. I could hear whispers. I could see parents pulling their kids a little closer.

I sat down on the stool, adjusted the microphone, and looked out at the crowd. “My name is Mike Reeves,” I said. “I’m Lisa’s dad. The only parent she’s got left. And she asked me not to come tonight because she’s ashamed of the way I look.”

The whispers got louder. I found Lisa in the wings. She was crying, her hands over her face.

“I don’t blame her,” I continued. “I know what I look like. I know I don’t fit in at school functions. I know other dads wear suits and ties and I wear leather and boots.” I paused. “But seven years ago, my wife died and left me with a six-year-old little girl who’d just lost her mama. And I had to figure out how to be enough for her.”

I started playing. Simple chords. The song I’d been working on for three weeks.

“I learned to braid your hair in the dark, baby girl. Learned to paint your nails without the mess. Learned to talk about the boys who broke your heart. Learned to be your mama and your dad.”

My voice cracked but I kept going. “You’re ashamed of me now, and that’s okay. Thirteen’s hard and fitting in matters more than anything. But baby girl, I need you to know—I’m not ashamed of you. Not ever. Not once.”

I could see parents in the audience crying now. But I was looking at Lisa.

“I’ve got tattoos from mistakes I made before you were born. I ride a bike that’s older than you are. I work with my hands because it’s all I know how to do. But these hands held you when you were born. These hands buried your mama. These hands learned to be gentle for you.”

The chorus was simple: “You can be ashamed of me, that’s alright. I’ll love you anyway with all my might. I’ll be here when the shame turns to pride. I’m your dad and I’m on your side.”

Lisa was sobbing in the wings. Other kids were crying too. Half the parents in that auditorium had tears streaming down their faces.

I finished the last verse. “Someday you’ll understand why I look the way I do. These tattoos tell stories and they’re all about getting through. And if you’re lucky, baby girl, you’ll know this too—the people who love you don’t care what you look like. They just love you.”

The final chord rang out in the silent auditorium. For a moment, nobody moved.

Then Lisa ran onto the stage. She threw herself into my arms and sobbed into my chest. “I’m sorry, Daddy. I’m so sorry. I’m sorry.”

I held my baby girl and cried. “It’s okay, sweetheart. It’s okay.”

The applause started slow and built until it was deafening. The entire auditorium stood up. But I didn’t care about them. I only cared about Lisa.

“I love you,” she sobbed. “I love you so much and I’m such a horrible person.”

“You’re thirteen,” I said into her hair. “Thirteen-year-olds are supposed to be embarrassed by their parents. It’s your job. My job is to love you anyway.”

She pulled back and looked at me. Her mascara was running and her nose was red. “Daddy, you learned to braid hair for me?”

“Watched about a hundred YouTube videos.”

“And you wrote that song?”

“Been working on it for three weeks. I’m not much of a singer.”

She hugged me again. “It was perfect. You’re perfect.”

After the show, parents I’d never met came up to shake my hand. Kids told me the song was cool. One father, a guy in an expensive suit, said, “You made me realize I need to spend more time with my daughter. Thank you.”

But the best part was Lisa. She held my hand walking to my truck. When we got to my Harley parked next to it, she said, “Dad? Can I ride home with you on the bike?”

“You sure? What about your friend’s mom?”

“I want everyone to see me with you.” She smiled. “I want them to know you’re my dad.”

I gave her my helmet and she climbed on behind me. As we rode through town, she held on tight and I heard her laugh. Really laugh. For the first time in months.

When we got home, she hugged me in the driveway. “I’m going to tell everyone at school about tonight. About how my dad wrote me a song and performed it in front of everyone.”

“Lisa, you don’t have to—”

“I want to, Dad. I want everyone to know how lucky I am.”

That night, she fell asleep on the couch with her head on my shoulder, just like she used to when she was little. I looked at her and thought about her mother. “I think I did okay tonight,” I whispered. “Our girl’s gonna be alright.”

And for the first time in seven years, I believed it.

My Daughter Scolded Me Not To Come To Her Talent Show So I Signed Up To Perform In It